Every story has a beginning, and every author has to drop a pin somewhere on the map of history and proclaim, “Here’s where it all starts.” For the story of the metroidvania subgenre, that map pin bears the name Zork. On its surface, Zork bears almost zero resemblance to the kind of game you usually find under the metroidvania header. It involves no platform jumping, no real combat—no action at all, in fact. You don’t kill monsters to gain levels, and you don’t equip progressively better gear to strengthen your protagonist. There’s certainly no auto-map. Basically, none of the features that normally go to make up the word “metroidvania” have any place here.

That is, with one exception. A lone exception that sits at the very core of the metroidvania concept even more so than the 2D barrel-hopping of Donkey Kong or the shooting platform action of Ghosts ‘N Goblins: the adventure game genre got its proper start here with this text-driven trip into an underground empire. Zork sends players wandering through caverns abandoned to time and forgotten by all but a handful of monsters (and one annoyingly persistent thief). At the time of Zork’s inception, no such designation or genre as “adventure games” even existed. The game’s creators, a group of programmers from MIT, had originally set out to create a video role-playing game, not an adventure. In a sense, they succeeded.

Zork stands apart from other early computer RPGs due to its creators’ focus. Most computerized takes on the RPG in the 1970s and ’80s (and, for that matter, now) revolved around the statistical elements of role-playing: experience points; gear attributes; and random, abstracted dice roll values. The ur-RPG, Dungeons & Dragons, evolved from miniature war games along the lines of Warhammer. When the genre made the transition to computers… well, you know, computers can’t tell stories, but they are really good at numbers. A random number generator works just as well as dice. And it’s so much less trouble to program all those complex conditional rules and combat modifiers than it is to commit them to memory! Thus, the computer RPG became an exercise in designing systems and processes, an excuse for combat and stat growth. Yet numbers ultimately comprise only half of the full RPG experience—

maybe less than that, really, if you really want to get to the heart of what role-playing truly means. A great RPG session turns on the art of storytelling; it lives and dies by the skills of its narrator. Will the game master send a group of friends through a combat meat grinder, or will they regale the party with an intricately constructed tale?

The problem with computers is that for all their skill with numbers, they’re not very flexible and lack any real spark of invention. Even if you believe the present-day hype about artificial intelligence, computers ultimately can only recompile existing data or churn through the text it’s fed. So, what happens when your party wanders off in a weird direction that the game master never accounted for? A talented GM will improvise and come up with something new, maybe something even better than what they’d originally intended. A computer will either churn out filler or simply give an error message before forcing you back on track.

Zork’s authors—Bruce Daniels, Dave Lebling, Marc Blank, and Tim Anderson—aimed to solve that question by creating an interactive text parser that could divine a player’s intent and respond with natural language. Of course, what they came up with was a matter of simple conditional statements, but it felt convincing enough to work. Zork was no match for ELIZA, the natural language processing computer from the ’60s, but it was sarcastic, descriptive, and adaptive. It painted pictures with words, gave players enticing clues, and let them figure out the world around them. It could remember what players had acquired, what they had done in the world, and what challenges they’d overcome. And, if players said something improper, it would respond with a chiding or even mocking remark.

However, it’s the world of Zork that matters most for our purposes. While Zork plays nothing at all like a metroidvania game in the “2D action platformer” sense, what those four geniuses at MIT created was, for all intents and purposes, gaming’s first nonlinear, persistent world that gated player progression by means of exploration and the application of tools. The workings of Zork don’t map directly onto something like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night; some obstacles in the underground empire work more as riddles than as tests of how effectively you’ve gathered and utilized equipment. For instance, no item will allow you to bypass the cyclops; instead, you simply need to figure out (somehow) that you need to speak the word “Ulysses” to get past him. In other areas, though, your advancement hinges upon determining how your collected items can be put to use to grant you access to new places. Need to descend a high, steep rise? Maybe that rope will do the trick. Need to get down a river? Well, you may have found a pump and a pile of plastic. What happens if you combine the two? And doesn’t that shovel seem like it would be good for digging in the sand?

Zork works best when it combines puzzle-solving with your inventory—like any good adventure game, really. Can’t figure out how to open the locked treasure egg without shattering it? Perhaps you should give it to someone whose vocation suggests they might be adept at picking locks. Like most games of its vintage, Zork does occasionally rely on unintuitive solutions and sometimes even pure guesswork. Particularly annoying is the thief, whom you need for certain solutions (like opening the treasure egg) but who has the potential to completely ruin your game if he randomly steals the wrong item or lucks into surviving your confrontation with him. But, you know, those are the breaks with pioneering works.

Zork’s fundamental innovations made it one of the most influential games of all time; even people who have never even heard of it draw on the concepts and mechanics it inspired. Of course, Zork had its own predecessors. Besides D&D, its creators also looked for inspiration to earlier works like William Crowther’s Colossal Cave Adventure, a.k.a. ADVENT. Zork’s creators drew heavily on that game’s cavernous structures and text-based parser when building their own world.

Still, Zork is where I’ve chosen to draw a line in the sand as the starting point for this particular historiography, simply because the contiguous world contained in the ruins of its Great Underground Empire was so much more intricate and persistent than the real-world caves mimicked by ADVENT. Solving Zork relied far more on player ingenuity and the creative application of tools and equipment, as well. There was even that meager little bit of combat with the wandering thief, which involved knowing your opponent’s weak point—namely, greed. While limited in many ways, and by no means an action-adventure game, Zork introduced a number of fundamental concepts that would become integral to the oddball little subgenre we call “metroidvania.” M

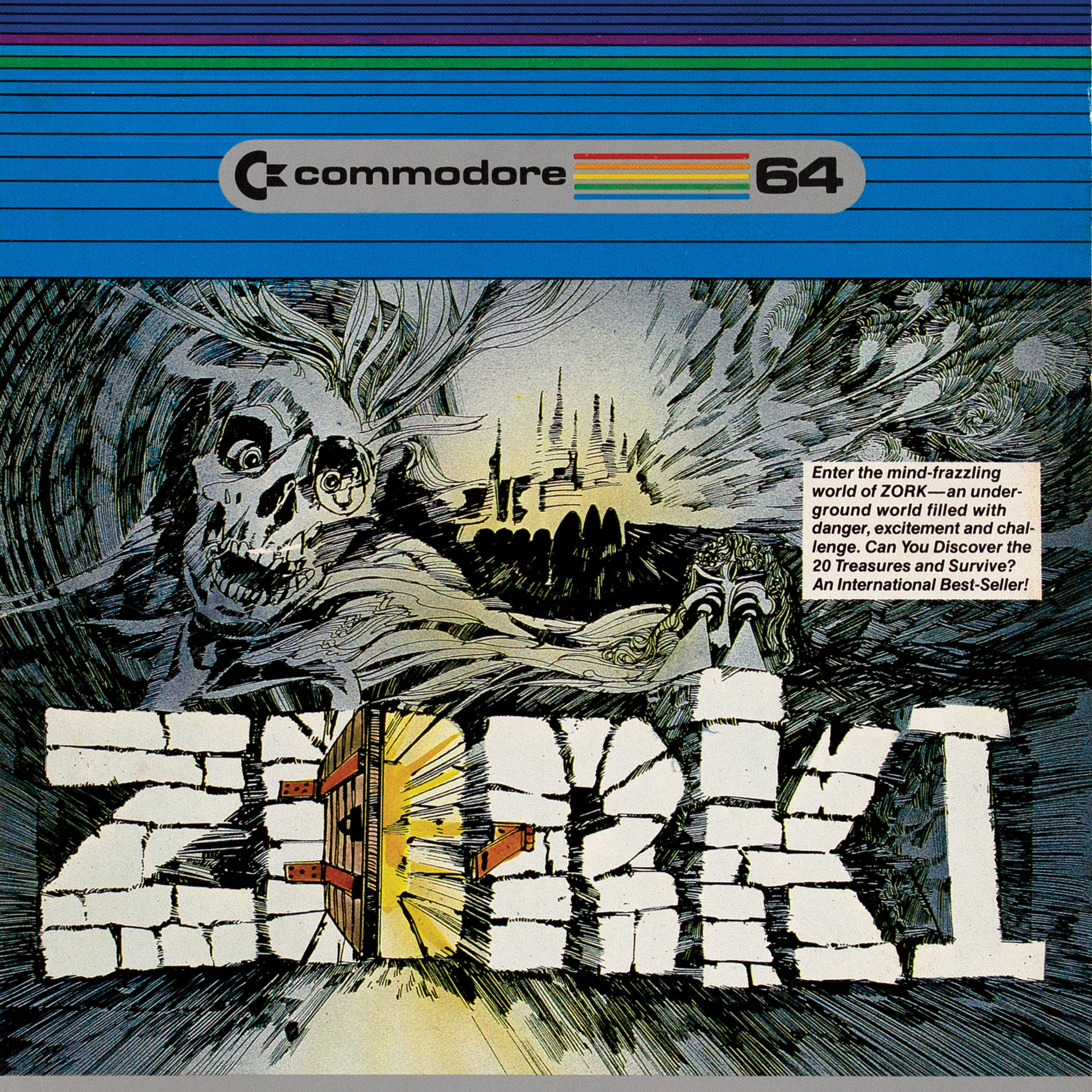

Platform: Mainframe and Personal Computers

Developer: Infocom

Publisher: Infocom

Initial release: 1977 [Mainframe] / Dec. 1980 [Microcomputer]